I recently had the privilege to be a social media guest contributor for the #alpinistcommunityproject. Over the course of a week last March, I shared a series of images that chronicled my journey to solo big-wall climbing.

I began my first post with an image from an unsuccessful big-wall expedition in Africa the previous year. In May, I had traveled to the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Principe, an island nation off the west coast of Africa, to attempt a first ascent on Pico Cão Grande: a needle-shaped volcanic plug that sits in a constant, thick cloud. I wrote in my first post that I was tremendously unprepared for the weeks ahead, as I stumbled through the process of learning to aid climb on a big wall in the thick of the rainforest. In later updates, I explained that, despite failures, obstacles and injury, I wouldn’t let anything cause me to lose sight of my new goal: to aid solo my first big-wall route after I returned home.

This comment appeared on one of the posts: Usually really like this climber spotlights but this one is a little over the top. “Such strength was always within me.” Gag me. Please let’s talk about rock and ice—not feelings.

The following week, Georgie Abel, a writer and yoga teacher in the Bay Area, shared excerpts from her recent book of poetry along with images of her climbing. In response, someone wrote: Wtf is all this spray lately. I thought this was a climbing magazine not a women’s issues blog. He later added: These Instacam climbing celebs absolutely nauseate me with their self aggrandizing emotional posts and shameless hawking of whatever book or sponsored product is paying their gas bill at the time. It’s extremely boring and I find it’s usually the female climbers who talk less about the rock and more about their feelings.

Something beyond the blatant stereotyping in one of the comments stuck with me: This is rock climbing it’s not supposed to be nice or safe or accepting of who you are and your ~feelings~.

As Reddit users have observed in the past, my own blog, a personal collection of stories that goes beyond ticking off projects to delve into the climbing lifestyle, generally “walks the line between poetic and overly saccharine.” After I released a short film called “For the Love of Climbing,” negative comments flooded the forum pages in response:

Why does every climbing video feature someone babbling about their philosophy/lifestyle/overcoming challenges/etc/etc. I don’t need a motivational speech from someone who lives in a van. I clicked on a climbing video to see some bloody climbing, just climb.

Yeah, I’m an asshole who, while spends a lot of time thinking about climbing (philosophy major…), also recoils against this… It’s climbing and you aren’t a better person because you do it and don’t have a moral high ground over people who prioritize work and “traditional” success.

I dirtbagged for a bit (all self-funded). I got some nice sends but it became depressing after awhile. Climbing is a leisure activity like golf; there’s nothing special about it.

Maybe I’m getting bitter as I get older, but I can’t stand all of this fake and manipulative altruism.

Everyone is on a journey to something. Weight loss journey, climbing journey, school journey. It’s tied in to people’s need to make mundane things seem extra important in their own little story. You’e [sic] right, climbing, at its core, is fucking stupid. I still don’t understand why I like it or waste my time with it.

Oh for fuck’s sake, what is with all this self-realization. Climbing is still as useless as it has always been. It’s not your fucking journey to enlightenment, it’s just…climbing.

Climbing doesn’t change you.

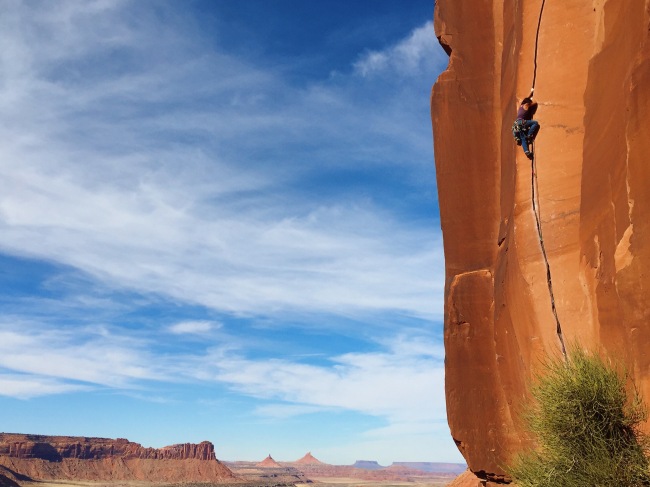

During my mid-twenties, much to my parents’ dismay, I moved into my car to pursue a life of rock climbing. My father, a mathematician and former college professor, made it clear that he disapproved of my guileless approach to life. My decision to quit my job and leave New York City was a final act of rebellion that didn’t make sense to my parents: they were both taught to work hard to achieve their goals and to live a modest life, not to follow whimsical dreams across the country. But for twelve months, I drove through the red deserts of Utah and Arizona and down old Wyoming country roads, fully embracing the dirtbag lifestyle with a belief that some truly satisfying things in life might still be free—companionship, love and laughter.

In the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, a deep and narrow chasm with mysterious, dark walls and an unwelcoming reputation, I found a wild nature that drew me, despite my fear. One evening, after five long days of climbing over shaded, pink-streaked granite, my partner and I tried to scrape our way to the North Rim before daylight expired. The skin on my hands was wrecked and raw. I felt exhaustion sinking into my bones, and I didn’t have much fight left within me, but the only passage out of the canyon was up.

We had two more pitches before we could crest the rim. I brought my partner to the belay station as the sunset flickered in the distance, darkness on its tail. I was afraid to lead the next pitch with only one small orb of light. But I racked up for it anyway, and as I entered the leaning crevice, I felt a strange and foreign sensation. It went as deep as it could into the cavity of my bones and nestled somewhere in my brain, sending vibrations throughout the rest of me. Then, with a single breath, I released my fear. My fingers tingled while I placed a piece of gear at waist level, my desire to gain the summit grew much greater than my apprehension, and I continued up.

Climbing weaves together personal experience and nature. It becomes an emotional exercise when we apply the lessons of scaling a rock face to everyday life. We don’t just reach the top for the sake of triumph, and how we get there counts for a lot. In her piece, In Climbing, as in Life, New York City cartoonist Connie Sun says: “One aspect of climbing is holding on with all of your strength. The other side, just as essential, is learning to let go to begin again.”

What is it about sentimentality that turns people away? A Dictionary of Literary Terms defines sentimentalism as “a superabundance of tender emotion, a disproportionate amount of…feeling.” Critics, as Robert C. Solomon explains in his book In Defense of Sentimentality, claim that sentimentalism distorts reality with “a ‘saccharine’ portrait of the world”: it manipulates the reader by appealing to what we generally consider shallow emotions, rather than exploring the “facts” of the story. When sentimental work plays with our feelings, it seems contrived and dishonest, a ploy to exploit our reactions. And many have declared that feelings have no place in climbing.

Yet we can trace strands of sentimental writing back to mountaineering’s early days. As the Canadian scholar Julie Rak explains, in eighteenth-century Europe, essayists and philosophers regularly invoked the trope of sentimentalism. “At the time,” Rak says, “it was called sensibility and it referred to investigating the world using the senses, which included feelings.” When explorers took to alpinism for science, they also kept notes on the inner effects of the experience. In A relation of a journey to the glaciers in the Dutch of Savoy (1775), the eighteenth-century mountaineer Marc-Théodore Bourrit observed that leaving the summit of Mt. Breven elicited deep pangs of regret: “We threw one parting glance over all those magnificent objects; which we never could be tired with surveying. We looked at one another, in expressive silence; our eyes alone could speak what we had seen, and told what passed in our hearts; they were affected beyond the power of utterance.”

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, sentimentalism became linked with women and the domestic realm. Nevertheless, sentimental writing about the Alps by some climbers, both male and female, persisted. In the Victorian Age, as David Robbins points out in Sport, Hegemony and the Middle Class, “For the romantic, the essence of mountaineering lay in an unmediated and intensely personal relationship between the individual and the mountains, on which competition and technicality were unwelcome impositions. Taken to its logical conclusion this implied the rejection of mountaineering as an organized sport and the radical recasting of its institutional practices and cultural traditions.” In other words, when mountaineering literature focuses on personal experience rather than on technical accomplishments, an author’s approach could be seen as subversive and, oddly, threatening to a status quo that valued things more easily measured and ranked.

Meanwhile, accusations of sentimentality began to appear in climbing publications. Published in 1883, Elizabeth LeBlond’s The High Alps in Winter was the first guide to winter mountaineering ever written in English. While LeBlond described some of her serious winter ascents, she tended to understate their actual risks; instead, she devoted more lavish prose to the beauties of the frozen landscape. That same year, an Alpine Journal reviewer noted: “After searching in vain for more satisfying matter, [the critic] has to remind himself that he is dealing with a lady’s book, and the book of a lady who has written to amuse an idle hour. Her narrative, he gladly allows, is simple, intelligible, and, as to difficulties and dangers, free from most of the exaggeration of tourists…. She has chosen to record them in a volume which is probably the flimsiest and most trivial that has ever been offered to the alpine public.”

The blanket dismissal of romantic writing is frequently imposed on women. As Brian Wilke points out in an article for College English, stories accused of sentimentality tend to be those with “a subject that involves not the grand emotions of the public hero but rather the intimate, intensely personal domestic emotions.” In other words, the sentimental is still often construed as a traditionally “feminine” and “inferior” realm. Similarly, in Poets & Writers, Nate Pritts notes: “Sentimentality is inherently seen as a weakness…. Critics use the term ‘sentimentality’ recursively, to indict writing that presents unwarranted sentiment, passages of unmoored or unjustified feeling.”

Male authors have, at times, also been subject to this criticism. In Eric Shipton: Everest and Beyond (1998), critic Peter Steele accused the famed mountaineer and adventurer of bouts of “purple prose.” Steele partially excused Eric Shipton’s offense, explaining that explorer was perhaps influenced by Frank Smythe’s “notoriously verbose” style. Still it would seem that, according to some modern mountaineers and critics, not only is there no place for feelings in climbing writing, there never was.

And yet emotionally saturated mountain literature maintains both defenders and practitioners. In his biography Shipton and Tilman, Jim Perrin argues that so-called “purple prose” is occasionally necessary: it represents “an attempt at expressing a mood that is essentially enraptured. It is a type of near-mystical perception.” Current climbers, too, try to capture spiritual or quasi-spiritual moments at altitude. In his essay, “Breathe Deep,” renowned alpinist Jeff Shapiro recounts, “By climbing in the mountains, I realize I’m small, insignificant and vulnerable. My ego crumbles, and my perspective expands. The borders between myself and my surroundings appear to dissolve…. I feel sunsets instead of merely seeing them: the ripening of their colors seems to evoke the scent of flower blossoms. A particular peace fills me, elusive, indefinable…. And [I] recognize how I fit into the natural world.”

The act of navigating with words through complex emotions has made me aware that what I’m doing goes beyond the technical movements of climbing. It’s about the elements, the seasons; it’s about life. It’s experiencing the quiet excitement of packing up a car and driving away, knowing that you will be gone for a very long time. Stumbling up steep switchbacks to giant granite cliffs that endlessly stretch on. Beating up every muscle in your body from sunrise to sunset, then watching embers glow in a dying campfire while you receive the last swig from the bottle making its way around. Taking a huge gulp of cool desert air and sinking into the calm of the evening. And waking up to do it all over again.

Despite a year of steady climbing, when I arrived in São Tomé in 2016, I felt both physically and mentally inadequate. After working for almost three consecutive weeks, both on and off the wall, our team of three dwindled to two when my partners told me that I should remain at the base. Filled with a sense of anguish and failure, I waited alone into the early morning hours as they made their push for the summit. Having already been dubbed an overly “sentimental” person in the past, I wondered whether being open about what happened on the trip and about my embarrassment would result in similar criticism. Perhaps exposing an instance of weakness implied that I wasn’t strong enough for this pursuit. Perhaps I was just another “female climber” who spoke less about the rock and more about her “feelings.”

Upon my return from São Tomé, I published an essay called “Do Not Go Outside to Cry.” I concluded: “Failure gives you depth. It gives you mental tenacity. It shatters the expectations we often feel trapped within, the expectations that our perceptions of ourselves create. Exposing our failures lets us fearlessly show the world that we are human…. Nobody walks up the mountain to the top with a smile on their face the entire time, or without shedding a few tears, a little blood.” I felt painfully exposed, but when readers responded to my story with benevolence, I realized why I had shared it in the first place: to cultivate empathy and understanding not only for myself, but for others who might have had an experience. I remembered that sentimentality helps me dwell in that sweet spot where I’ve encountered something so big that maybe words will never do it justice. That feeling is humanizing to me, and it’s there, in the act of vulnerable writing, that I see the importance of honesty.

In the past, like many climbers, I was reluctant to accept that vulnerability wasn’t always a flaw. I believed that strength meant wearing a ten-ton shield of mental toughness and achieving perfection in all aspects of life, from my relationships to my climbing goals, and everything in between. I’d convinced myself that my value was based on my accomplishments. Over time, however, my fear of rejection and judgment morphed from a shield into an encumbrance. It was then that choosing vulnerability became an act of courage.

For me, anything powerful enough to awaken sentiment is worth a dialogue. Such conversations can build intimacy with others, a sense of overlapping stories: even on Instagram and Facebook, I like to think of my words as tiny notes and letters between pen pals I have yet to meet. Perhaps sentimentality is not a distortion of the real world, but something that allows us to see life from a different perspective. It’s an appeal for feeling things freely without censoring our own tenderness. From love songs to great literature, it is the sense of love and happiness, pain and suffering, empathy and compassion, that transforms us. The way the earth looks after rainfall, sopping wet and glinting with newness, stays with me long after the moment is gone. The sound of gear clanking above as I hold the belay rope in my hand. The fear before an airy fall, and then the sudden sensation of taking the plunge. The sweet smell of sagebrush that always reminds me of Wyoming.

Any person who thinks that it’s a waste of time to treasure these things is welcome to their opinion, but they’re missing out. We all have emotions that eventually bring us to self-awareness, if we let them. Beneath every curmudgeonly old soul is the ability to share a passion and appreciate something that makes us feel deeply, often in ways we can’t quite explain. It’s true—climbing does not change you. But having a passion for something is what will.

This article was originally published in Alpinist Magazine Issue 61 – Spring 2018